BUILDING IN CIRCLES: COMPOSITE RECYCLING PARTNERS WITH BENETEAU

Recycling end-of-life composite boats or the production waste from composite boat building has been a subject of interest at IBEX and Professional BoatBuilder during the past decade. As with many emerging materials and processes, we started with experimental projects and proof-of-concept prototypes including the promising potential for composites made from thermoplastic resin to be recycled.

For the most part that meant grinding the clean thermoplastic composite waste into a material that could be included in new composite structures. But the ability to break down the resin at a molecular level allowing for reclamation of fibers and resin separately, remained largely a theoretical possibility with no industrial-scale application…until now. Last month, a coalition of boatbuilders, waste experts, and composite and chemical companies announced an operating circular economy model for marine composites manufacturers.

They include French boatbuilding giant, Groupe Beneteau; Veolia, a global leader in waste management and environmental services; composite-waste-recycling startup, Composite Recycling; Arkema, a French coatings and materials company; fiberglass manufacturer, Owens Corning; and Chomarat, specialists in technical textiles and composite reinforcements. The project, based around Beneteau’s production facilities in Western France, is currently limited to production waste from models built with Arkema’s Elium thermoplastic resin. By subjecting the cutoffs and trim to Composite Recycling’s thermolysis process, oil from the resin and clean fibers (glass or carbon fiber) can be reclaimed, returned to the resin and textile manufacturers, reformulated or rewoven, and delivered back to Beneteau to build new boats.

The Disposal Conundrum Last week, I spoke with Guillaume Perben, co-founder of Swiss-based Composite Recycling about the genesis of the project, which holds promise for marine and other manufacturing sectors facing regulatory and market changes that have boosted the demand for composite solutions and simultaneously presented obstacles to their adoption. In this instance, it’s the boatbuilders who are leading the development. It started in 2021, Perben said, as he and his naval-architect brother contemplated the long-term fate of their 30′ (9.1m) fiberglass sailboat. The landfill seemed the most likely final resting place, but Perben knew how much entrained energy and still useful chemicals and fiber would remain in the hull structure. After decades in business development and restructuring in the automotive sector, he had worked most recently for a tire-recycling effort that relied on pyrolysis (heating in excess of 500°C/ 932°F) to reclaim useful material (gas and oil) from discarded rubber. “I asked, ‘Would that technology for the tires work for composites?’” he recalled.

For an answer he turned to Véronique Michaud who leads the Laboratory for Processing of Advanced Composites at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland. She told him it was possible and relatively common knowledge, but when Perben checked with some naval architect friends, they were in the dark and very interested in knowing there was a solution to the growing challenge of composite boat and production waste disposal. “We saw such a gap between the industry and the science,” Perben said. He went back to Michaud who lent him some engineers and a small thermolysis machine to prove the technology. By the end of 2021 he and his colleague Pascal Gallo had founded the company, raised some funds, and built their first machine for testing real-life samples of composite materials to determine their recyclability.

While the technology was sound, Perben knew they would have to prove the value chain to customers to stay relevant. To date the company has conducted about 500 tests, he said, mostly for automotive, aerospace, and associated industries. They have about 50 commercial clients who rely on Composite Recycling to prove that switching to composites doesn’t make a product less recyclable. For instance, if a supplier is looking to replace steel leaf springs in automotive suspension with composite structure, the car builder might balk at the shift because they need to make as much of each vehicle recyclable as possible. Composite Recycling can document and quantify the recyclability and carbon footprint of the composite option. Perben noted that shifts in the regulatory landscape prohibiting disposal of composite waste at landfills in many European countries pushed the company to focus on production waste not disposal of derelict boats.

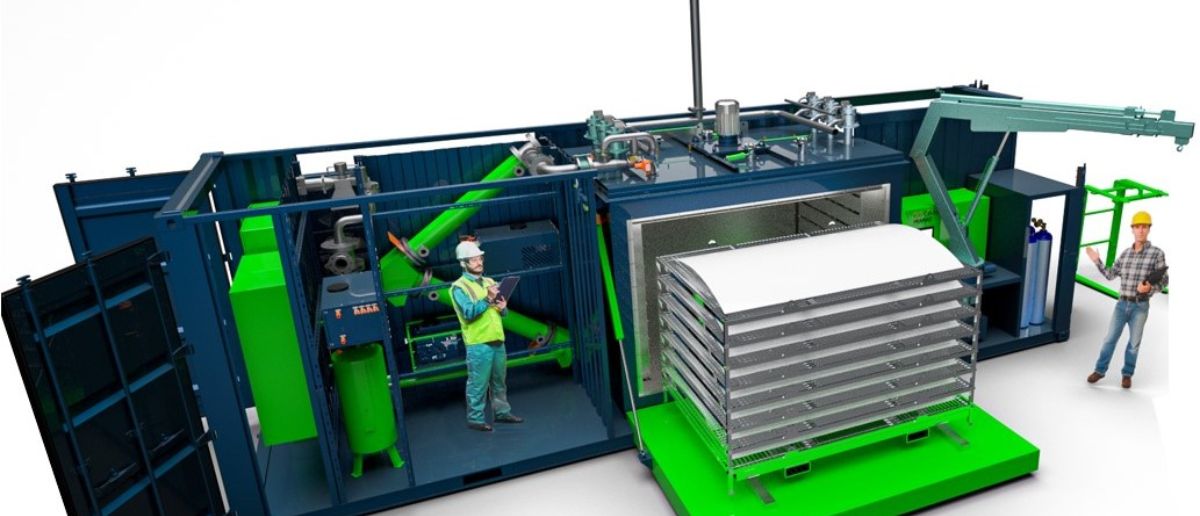

The latter challenge remains but is complicated by the unknowable chemistry that enters the waste stream in the form of anti-fouling coatings and other contaminants on a well-used boat. “We will be able to recycle old boats someday,” he said, but “production scraps are the priority now.” Portable thermolysis unit. Courtesy Composite Recycling The 30′ (9.1m) portable thermolysis units can process 400 tons of composite waste annually. Test-drive at Beneteau This gets us back to the Beneteau project, fueled by the boatbuilders’ desire to limit or eliminate composite waste from production.

Because the waste is uniform and its content predictable, Beneteau’s challenge suits Composite Recycling as they scale and fine-tune their recycling process. “We started with the Elium-based composites because we had excellent results with that resin,” Perben said. Conveniently, Beneteau is producing at least one model line using that chemistry from Arkema. “Our Jeanneau Sun Fast 30 One Design models and, more recently, Beneteau Oceanis Yacht 60 perfectly illustrate that circular manufacturing in the nautical sector is no longer a simple goal, but a tangible reality,” said Erwan Faoucher, Vice President Innovation & Sustainable Development of Groupe Beneteau in the project announcement. As composite waste comes off the production line at Beneteau, it is cut into flat sections and consigned to specific containers for disposal. Waste-management company Veolia trucks the scrap to a nearby site where a portable thermolysis unit from Composite Recycling has been installed. The 30’ (9.1m) containerized machine can process 400 tons of composite waste annually and can be moved over the road to whatever location is most expedient as production needs shift.

Perben: “We open the oven—imagine a 2m x 2m x 2m pizza oven with racks. We put the flat pieces on the racks, but they are not piled up…we need the heat to circulate between the layers of composites.” The 500 kg (1,102 lb) load cooks for between three and four hours. “You heat it with no oxygen,” Perben explained. “That means there is no combustion. Instead of burning, the resin (the plastic part) is vaporized. Then we condense that vapor to get different levels of oil.” He said the yield from the Elium composites include over 80% of the N-methylolacrylamide (NMA) that went into the resin. Arkema picks that distillate up to reuse in new Elium resin that goes back to Beneteau for the next round of production. Similarly, the calcinated glass fibers go to Owens Corning’s new plant powered by hydro power from the Rhone River, to be melted and spun into new fiber to be woven into fiberglass roving for use back at Beneteau. That’s the simplified version. In truth there’s uncertainty and nuance to the process as they develop techniques and practical measures to meet client demands.

For instance, Perben noted that the waste from Beneteau includes polyester-based gelcoat on the Elium hull laminates. “By working the treatment parameters (timing and temperature), we manage to separate these two, so we get oil from polyester in one tank and oil from Elium in the other.” Beyond Thermoplastics Perben is clear that while Elium resin is the easiest for the Composite Recycling mobile units to process right now, the technology can successfully reclaim elements of epoxy- and polyester-based laminates as well. He explained that the thermolysis process can yield a diesel-fuel equivalent from polyester resin, but the resulting fuel would not be approved for combustion in Europe. But by fussing with the treatment parameters again, they can extract phenol from epoxy composites and styrene from polyester. “Those are very interesting to make new plastics,” he said.

And plastic can be recycled as many as eight times. That’s significantly better than burning the distillate as diesel fuel once. Perben said ideally the evolving recycling technology would become part of the design and build planning, informing choices of coatings and core materials as well as fiber and resins. “If you’re smart with the way you build your new boats that means they will be less expensive to recycle. That means the extra cost for you as a producer of waste is reduced,” he said. With luck there will come a day when he could recycle his boat that inspired the project. For now, he said, that boat’s still sailing.

Source: Proboat.com